Prologue

In the early Fall of 2020, Turkey unleashes millions of refugees into Europe and Syria making good on threats made since its invasion of northern Syria in October 2019. President Erdogan has also forcibly repatriated hundreds of foreign terrorist fighters and their families to European nations previously unwilling to accept the return of their nationals. Finally, Erdogan has requested North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) Article 5 assistance in defending Turkey from armed attacks from Syria. NATO is facing its worst threat since the cold war but is unable to act as NATO member-states begin taking individual steps to secure their borders against the onslaught of refugees and foreign terrorist fighters. Violent extremist organizations present in the refugee populations take advantage of the chaos created by the mass movements of Syrian refugees and regain physical control of territory within Syria and Iraq. President Putin begins exerting pressure on former eastern bloc and Middle Eastern nations to reform a regional security and economic alliance with Russia.* The upcoming American election has paralyzed Washington and the United Nations (UN) continues to be hamstrung by Russia and China. Can NATO survive this threat? Will NATO assist Turkey? Will the United States defend its vital national security interests in NATO? Will Russia and Iran reassert themselves as the dominant regional players in the Middle East? Will there be a resurgence of yet another violent extremist organization in the region? This fictional scenario is not only plausible, but components of this scenario continue to play out in the news headlines week by week.

* Jim Mattis, “Summary of the 2018 National Defense Strategy,” page 8, available at https://dod.defense.gov/Portals/1/Documents/pubs/2018-National-Defense-…, accessed November 19, 2019. (“A strong and free Europe and a shared commitment to NATO is a vital national security interest of the United States.”).

1. Introduction

The United States will soon be faced with new national security threats arising from conflict zones in and around Syria. These conflicts have created large displaced populations capable of being weaponized along with mobile safe havens. It is within these populations and havens that the next violent extremist national security threat will be conceived and grow unimpeded if not systematically addressed.

Syria is one of the most intractable problems facing the international community since World War II. The United States has stayed on the fringes of the conflict maintaining diplomatic pressure through reactive negotiations and military pressure through limited counterterrorism operations. This approach has failed to adequately address larger national security threats flowing from the conflict—that of the use of weaponized populations and mobile safehavens now present throughout the region by violent extremist organizations. To date the Syrian conflict has displaced eleven million persons. These displaced populations are inundated with foreign terrorist fighters and violent extremists. These populations have migrated into Europe and changed the political landscape of the countries where they settled. These populations are also situated in ungoverned spaces within Syria and in all countries bordering Syria.

The resurgence of Islamic State of Iraq and Syria (ISIS) or the next evolution of violent extremist ideology will undoubtedly flow from this region. Regional and global actors have protracted the conflict and stymied the peace process. This paper is not an exposé on the plight of Syrian refugees nor is a plea to rebuild Syria. Instead, this paper discusses the national security threat components of weaponized populations and mobile safe havens used by violent extremist organizations and offers policy recommendations to support a long-term strategy to reduce violence in the region, contain these new threats, and set conditions for reconciliation and peace.

2. Historical Inflection Point: National Security Threats Posed by Syria and Weaponized Populations

The Syrian civil war is a historical inflection point for the Middle East and Europe given the humanitarian scale, geographic impacts, and generational effects of the conflict. The Syrian civil war and operations against ISIS have forced more than half of all Syrians to leave their homes, making Syria the largest displacement crisis globally.1 Unfortunately, the Syrian problem can’t be addressed solely through international refugee mechanisms because in Syria and surrounding countries, displaced Syrian populations have been weaponized.

Weaponized populations are defined as populations that are adapted for use as a weapon of war or to achieve coercive political goals short of war.2 Syrian refugee populations should be considered as weapons for the following reasons. First, refugee populations are inundated with foreign terrorist fighters and violent extremists who have converted these populations into mobile safe havens dispersed throughout nations bordering Syria. Second, refugee populations pose a coercive threat given the sheer size and scale of displaced populations that makes any mass migration event of those populations a potentially catastrophic national security and humanitarian event. Third, geographically poised weaponized populations have the potential to destabilize host nations, the region, and contribute to conflict for decades unless they are contained.

The main problem facing the United States isn’t the Syrian civil war, or the refugee crisis, or the resurgence of ISIS. The national security problem that needs to be addressed by the United States is the weaponized population and mobile safe havens that were created as a result of conflicts throughout the region. It is within these populations and havens that the next violent extremist national security threat will be conceived and grow unimpeded. This is where the United States must apply a long-term strategy to contain these threats before they pull this country into yet another protracted conflict or culminate in another attack on the United States.

3. Weaponized Population National Security Threat Components

Violent extremist organizations thrive in displaced populations for a number of reasons. Those reasons also contribute to the overall national security threat posed by these populations. Conceptually think of the threat components of weaponized populations as layers of risk. Each component raises the overall risk and threat posed. I have binned these risked into four components and will discuss each one in detail.

3.1 Location and Size

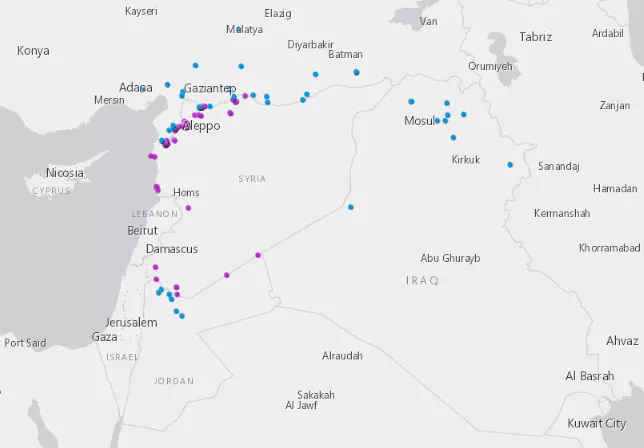

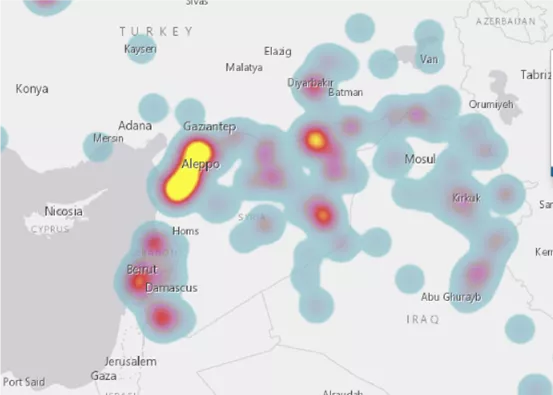

Displaced populations are not just dots on a map but occupy defined geographical areas. These geographical areas lie along major geographic, cultural, political, and religious fault lines surrounding Syria. In essence the areas occupied by weaponized populations form a ring of fire around Syria acting as a significant destabilizing force throughout the Middle East and Europe. Violence in the region creates more displacement and more potential violent extremist energy is being stored up in these populations.

Syrians have settled in Internally Displaced Persons camps within Syria and Refugee camps in every nation bordering Syria with the largest concentrations in Turkey, Jordan and Iraq.

Violent extremists understand the geographical and strategic importance of displaced populations. The size of these refugee population clusters scattered throughout the region provides violent extremists with opportunities to reconstitute within the ungoverned spaces created by the conflict and mass migration of the Syrian population. Moreover, as camps continue to swell in numbers, violent extremist recruiters have a ready-made pool of recruits. Violent extremist ideology can more easily permeate refugee populations given their density and inherent lack of governance. Furthermore, the precursors for violent extremism can run rampant in these at-risk populations. With limited access to basic necessities, few opportunities for education, and lack of employment alternatives, violent extremist organizations offer an attractive alternative to a lifetime of hardship in a refugee camp. Violent extremists understand how to effectively use ideology mixed with fear to compel cultural adherence and large-scale action. The size and location of these weaponized populations forms the foundation of the potential national security threat posed. Three additional components described below increase the nature and immediacy of the threat for the region and the United States.

3.2 Composition

Over 40,000 Foreign Fighters and affiliates went to fight for ISIS in the region. Only a fraction of these fighters have been repatriated, leaving the vast majority to integrate into the IDP and Refugee populations clustered around Syria’s borders.

Syrians comprise most of the displaced populations. The conflict with the ISIS added an additional level of complexity to the Syrian refugee crisis and significantly increased the threat posed by weaponized populations as members of this violent extremist organization integrated into refugee populations as the conflict with ISIS abated. More significantly, within the past five years, ISIS recruited large numbers of foreign terrorist fighters, over forty thousand from 120 different countries, and few have returned or been repatriated.3 Once ISIS was defeated some foreign terrorist fighters were held in Syria, some returned or were repatriated, and the vast majority to include women and children have integrated into refugee populations throughout the region.4 To date, of the 50,000 foreign affiliates of ISIS in Syria, only an estimated 8000 have been successfully returned to their countries of origin.5 The addition of foreign terrorist fighters to these populations increases the threats posed by these weaponized populations exponentially.

Adding foreign terrorist fighters to the composition of weaponized populations surrounding Syria increases the threats posed by these populations because foreign terrorist fighters are highly motivated by violent extremism. Their motivation is coupled with military expertise that invariably escalates into violence wherever foreign terrorist fighters are found. UN Security Council Resolution (UNSCR) 2178 (214) defines “foreign terrorist fighters” as “individuals who travel to the State other than their States of residence or nationality for the purpose of perpetration, planning, or preparation of, or participation in, terrorist acts or the providing or receiving of terrorist training, including in connection with armed conflict.”6 Others have defined foreign terrorist fighters simply as “noncitizens in conflict states who join insurgencies during civil conflicts.”7 Foreign terrorist fighters have been seen in conflicts around the globe since the inception of modern warfare. David Malet’s book entitled Foreign terrorist fighters: Transnational Identity in Global Conflicts, maps the use of foreign terrorist fighters from the 1800s to date. Malet’s research indicates two troubling trends. First, the numbers of foreign terrorist fighters participating in conflicts is on the rise.8 Second, conflicts are more lethal and intractable where foreign terrorist fighters are present.9 We have seen these trends at an all-time high in the conflict with ISIS in Syria.10

The United States National Defense Strategy indication that “the significant numbers of foreign terrorist fighters taking part in the conflict in Syria represent a profound increase and pose significantly greater threats to U.S. national security.”11 This position is echoed by the UN describing the threat posed by foreign terrorist fighters as “evolving rapidly and unlikely to be fully contained in the short term.”12 Further the UN stated that “[foreign terrorist fighters] increase the intensity, duration, and complexity of conflicts and may constitute a serious danger to their States of origin, transit, destination, as well as neighboring zones of armed conflict in which they are active.”13 The conflict in Syria has changed the nature of the threat posed by foreign fighters and refugees because these populations are now combined. For example, in just one camp in Syria this year of the 75,000 inhabitants, over 25,000 were foreign fighters and their families.14 These combined populations are large enough that any mass movement of those populations would impose significant hardships on bordering nations not prepared to address the scale and scope of humanitarian and security problems presented by such large scale population movements.15 Conceptually, the threats posed by refugee populations remained remote to Europe until Turkey began threatening to push hundreds of thousands of refugees into Europe and forcibly repatriate hundreds of radicalized and battle-hardened foreign terrorist fighters.16

Now there is renewed impetus to achieve a resolution to the conflict that addresses these weaponized populations including the foreign terrorist fighters resident therein. There are two additional components of the threat posed by weaponized populations that provide impetus for sustained action.

3.3 Mobile Safe Havens

Consider now the threat potential of large heterogeneous Syrian refugee populations that we have been discussing as unconfined geographically. They are also at risk ideologically and practically ungoverned. These populations fit the traditional definition of a safe haven. Specifically, the United States defines terrorist safe havens as “ungoverned, under-governed, or ill-governed physical areas where terrorists are able to organize, plan, raise funds, communicate, recruit, train, transit, and operate in relative security because of inadequate governance capacity, political will, or both.”17 Syrian refugee populations can be considered mobile safe havens because of their size and proximity to conflict zones and ungoverned territories as well as the integration of violent extremists and foreign terrorist fighters. They can be considered mobile because these populations live in temporary camps. They can be uprooted and forced to move at any moment as demonstrated by displacements caused by fighting near Idlib and Turkey’s move to open its’ borders to force migration through Turkey instead of into Turkey.18 The scale and scope of these populations in relation to ungoverned spaces promotes use by violent extremist organizations in all aspects of the terrorist safe haven definition listed above.

The United States National Security Strategy lists elimination of terrorist sanctuaries as a top counterterrorism action.19 Retired General Joseph Votel and other United States senior leaders warn about the threat of violent extremist organizations once again using the region to establish safe havens to conduct training and as a platform launch attacks against the West. The prevention of terrorist safe havens has been a United States national security objective since 9/11. It remains a top national security objective of the United States as outlined in the 2018 National Defense Strategy for the Middle East, where “[the United States] will foster a stable and secure Middle East that denies safe havens for terrorists, is not dominated by any power hostile to the United States, and that contributes to stable global energy markets and secure trade routes.”20 The weaponized populations and mobile safe havens created as a result of the Syrian conflict undermine these objectives. As Henry Kissinger recently commented, “[m]aking sure that this territory [Syria] does not become a permanent terrorist haven must have precedence.”21

The remnants of ISIS have dispersed and integrated into displaced Syrian populations. Violence now rings Syria. The next Violent Extremist Threat will evolve from these areas populated with at risk populations that can be both weaponized and serve as mobile safe havens.

The threat of the resurgence of ISIS from the mobile safe havens in and around Syria is imminent. History has taught us that violent extremists no longer depend on the possession of territory for legitimacy22 The world has seen this play out with the global nature of Al Qaeda and ISIS. Modern communications enable violent extremist organizations to exist and flourish in virtual environments while consolidating power and control geographically in at-risk populations around the globe. In Syria, ISIS is reorganizing. As Assad continues his push into rebel-held territories in northeastern Syria, tens of thousands of ISIS prisoners and thousands of foreign terrorist fighters are at risk of being released by retreating rebel forces.23 “If security collapses, hardened fighters may escape the prisons and reengage with the 18,000 fighters in Islamic State cells across Iraq and Syria to help fuel an already-burgeoning Islamic State resurgence.”24 If this happens, ISIS will likely supplant the opposition in Syria as the main threat to the Assad regime.

While location, size and composition of weaponized populations surrounding Syria present significant threats, there are additional threat multipliers present in the region that factor into the policy calculus for United States. These threat multipliers are grave because threaten key United States alliances, run counter to United States security interests, and act as additional destabilizing forces in the region.

3.4 Strategic Threat Multipliers

Weapons of Mass Destruction (WMD)

Countering the proliferation of weapons of mass destruction remain a top United States national security priority.25 ISIS sought both WMD and associated technical expertise and will continue to pursue them as long as safe havens exist.26 Violent extremists who are integrated into weaponized populations around Syria will continue to attempt to acquire, develop, and use WMD.27

Iranian and Russian Influence

Countering Iran and Russia remain top United States national security priorities.28 The influence of Iran and Russia throughout the region cannot be understated. Iran continues to contribute to the conflict in Syria and seeks to obtain transit routes to support Lebanese Hezbollah.29 Russia supports the Syrian regime and seeks to maintain a forward presence in Syria.30 Both of these State actors view Syria as a strategic opportunity to offset United States influence in the region while maintaining access to key geography in and around Syria for power projection and logistical support for terrorist activities.31 Displaced populations have become pawns in a game of regional influence. Threats of putting displaced populations on the move or denying funding or entry for humanitarian aid have become negotiating tactics of these nations. This approach is being adopted by other authoritarians in the region with Turkey adopting a similar approach with the European Union.32 These approaches significantly increase the risks posed by weaponized populations because they increase uncertainty and keep these populations transient.

Turkey and NATO

Defending NATO is a vital United States national security interest.33 The rise of Turkey as a dominant player in the Syrian conflict has increased tensions within the region but has the potential of pulling NATO into a conflict with Russia and Syria.34 Turkey and Syria have stopped fighting through proxies and are now directly attacking each other.35 Not only has Turkey entered into the Syrian conflict, it also hosts 3.6 million Syrians displaced by the conflict. This mass migration has destabilized the government and economy of Turkey. The European Union has criticized Turkish attempts to address the Syrian refugee and violent extremist problem now present in their country.36 As a result, Turkey has threatened to unleash Syrian populations and foreign fighters on Europe37 with the tacit understanding that Europe only pays attention “when they are threatened by the influx of refugees.”38 Recently, has opened its’ border with Europe to permit the transit of additional refugees through Turkey into Europe.39 Turkey is also establishing a safe zone to resettle Syrian refugees in and act as a buffer against Kurdish entities they view as terrorist organizations.40 In essence, Turkey is contributing to the weaponization of the Syrian refugee population and creating additional large-scale safe havens for violent extremist organizations.

4. United States Foreign Policy Recommendations

United States foreign policy towards the Middle East remains problematic given the history of the region’s relationship with the West and other major powers. Today, there is no one regional power that can unite the nations of the Middle East regarding Syria. (There are opportunities to work on old alliances and threats to spur action). Countries have applied various international and domestic legal standards and exercised disparate self-interested foreign policies while the scope of the Syrian crisis continues to grow.

The United States has taken a pragmatic narrowly tailored foreign policy approach with Syria, maintaining a military presence to facilitate counterterrorism operations, supporting limited repatriation of foreign fighters, and providing refugee assistance through the United Nations. Washington’s approach is also constrained by the ever-changing cast of regional allies and partners willing to support concerted action in the region and association with the United States.41 Our counterterrorism approach placates the various regional stakeholders but fails to address the underlying problems that contribute to the rise of violent extremism in the first place. Moreover, this light touch approach fails to holistically address the violent extremist threats operating within displaced populations throughout the Middle East. Simply put, twelve years of civil war in Syria and the dissipating war against ISIS in the region have left in their wake a human catastrophe that is now a global strategic threat multiplier that must be addressed.42 The foreign policy options listed below outline a long-term approach that reduces violence in the region through economic and military containment to enable conflict resolution and reconciliation while reducing the precursors for future conflict.

4.1 Lead or Support UN, NATO, or Regional Efforts to Negotiate Cease-Fire and Peace for the Syrian Conflict

The United States should use the external and internal threats posed by weaponized populations and mobile safe havens to supplant the Assad regime’s focus on the opposition for an even greater threat of the resurgence of a violent extremist organization that could undermine the regime.

Negotiate Peace through Common Ground

A resolution of the Syrian conflict must be negotiated. The United States should lead, or in the alternative, encourage the United Nations and NATO43 or a new Middle Eastern coalition to lead efforts to negotiate a Syrian peace. All nations including Syria fear the resurgence of ISIS or another violent extremist organization bent on establishing a physical caliphate. The United States should use the external and internal threats posed by weaponized populations and mobile safe havens to supplant the Assad regime’s focus on the opposition for an even greater threat of the resurgence of a violent extremist organization that could undermine the regime. The United States will have to negotiate with Assad and can leverage mutual security interests between Washington, Moscow, and Damascus in countering violent extremism in Syria as common ground for negotiations.44

Reduce Violence through Ceasefires

Cease fires can set the conditions for renewed talks among the key power brokers. Cease fires also reduce the displacement pressure on weaponized populations

Limited ceasefires between Syrian and opposition forces can facilitate these negotiations. Turkey as member of NATO, can contribute to the reduction in violence because of its’ unique relationships with the both the United States and Russia. Turkey should not be allowed to continue to negotiate with Russia and Iran on a limited ceasefire in northern Syria.45 Iran contributes to instability throughout the Middle East. Instead, cease fires can set the conditions for renewed talks among the key power brokers. Cease fires also reduce the displacement pressure on weaponized populations.

Use Reconciliation of Syrian Detainees to Set Conditions for Future Peace

Components of peace process must offset Iranian influence in Syria, enable repatriation and reintegration of all Syrians displaced by the conflict, and facilitate reconstruction of Syrian infrastructure and civil society. Foreign terrorist fighters and ISIS detainees remaining in Syria should be subject to Syrian pluralistic civil or criminal legal process. While many in Washington consider this as a perilous option, prisoner exchanges with assurances and international monitoring can help build trust and take additional pressure off of the opposition who hold most detainees in Syria. The Assad regime can also demonstrate commitment to the rule of law with this initial step in a long-term reconciliation process. Finally, building upon gains made by the United Nations during recent Syrian Constitutional Committee talks46, countries adjacent to Syria supporting significant populations of refugees should form a new coalition to drive the peace process through economic leverage gained by the imposition of policy recommendation two below.

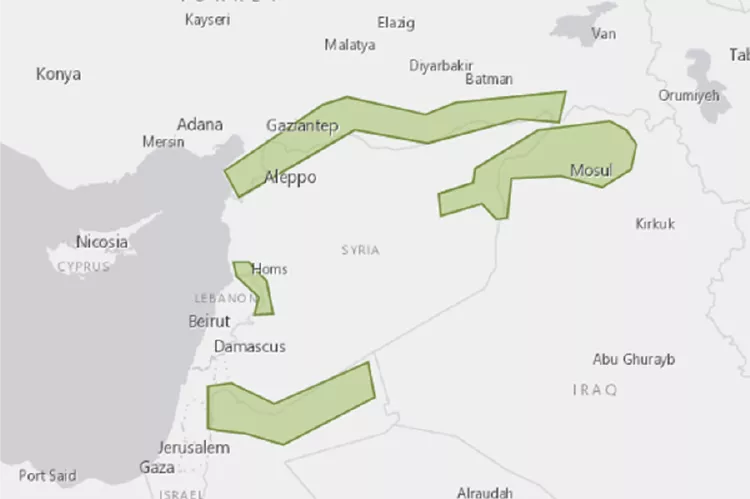

4.2 Support Establishment of Special Economic Zones in Jordan, Syria, Turkey, and Iraq

Special Economic Zones (SEZs)

SEZs should be established and expanded throughout the nations surrounding Syria given recent evidence indicating that these zones dramatically improve the lives of both refugees and host nations as well as the role these zones play in preventing the resurgence of violent extremism. SEZs are zones in designated geographic areas where governments offer economic incentives to promote development, attract foreign direct investment, and provide employment opportunities.47 SEZs can be used to address root causes of violent extremism by extending banking and financial services to economically and politically isolated regions and marginalized groups.48 SEZs enable nations to realistically address the economic realities on the ground that are beyond the scope of traditional humanitarian assistance programs.49 “Recognizing the protracted nature of displacement, host countries are taking steps toward finding solutions for refugees and their host communities. Governments are beginning to acknowledge the benefits of incorporating refugees into development plans and investing in the ability of refugees to contribute to local economies—in discernable contrast to the traditional camp-based, external actor model of supporting refugees”50 Supporting SEZs in all of Syria’s neighbors strengthens bilateral relationships through trade and puts refugees on an economic path to recovery.

Putting refugees to work shifts the ways States think about refugees from economic burden to economic growth engine. Refugees become valuable assets, contributors to society, and strategic buffers that reduce conflict.

SEZ Implementation through Compact Agreements

Europe has implemented the SEZ concept through a “Compact Agreement” model that enables the international community, host governments, and individual donors to implement new economic development approaches at the country level. The compacts also “bring together host countries, donors, and development and humanitarian actors in a multiyear, mutually accountable agreement to achieve outcomes for refugees and host communities.”51 Specifically, Europe negotiated Jordan and Lebanon compacts in 2016 that obtained commitments from public and private donors, development agencies and NGOs, and the governments of Jordan and Lebanon to establish SEZs. “In Jordan, the compact seeks to create 200,000 new job opportunities for refugees, primarily by developing and strengthening existing SEZs and by relaxing rules for exports to the European Union (EU) to attract international and domestic investments and spur job growth.”52 The SEZ in Jordan is achieving results not only for Syrian refugees but for the entire Jordanian economy.53 Replicating this concept to all nations surrounding Syria can provide economic leverage necessary to both reduce conflict and spur additional economic growth within Syria as reconstruction begins.

Threats posed by weaponized populations and mobile safe havens are mitigated as the populations settle into a more permanent geographic regions and stabilize economically.

SEZ and EU Compact Expansion to All Countries Hosting Syrian Refugees. The SEZ concept should be expanded to Turkey and Iraq through new compact agreements negotiated by the EU. “[i]nstead of insisting on returning refugees to Syria (further weaponizing these populations), Turkey should — together with the EU — explore policies to help them become more self-reliant and productive members of the Turkish economy.”54 Putting refugees to work shifts the ways States think about refugees from economic burden to economic growth engine. Refugees become valuable assets, contributors to society, and strategic buffers that reduce conflict. From the weaponized population and mobile safe haven perspective, these threats are mitigated as the populations settle into a more permanent geographic regions and stabilize economically. Use of SEZ concept with Turkey also aligns with recent U.S. foreign policy discussions with NATO regarding increased spending to defend NATO.55

By contributing to expanded compacts to establish socio-economic zones, NATO countries can demonstrate value to the international community and at home by mitigating risks without the employment of force or collective self-defense. A Turkish SEZ would also bring Turkey back within NATO away from Russia. SEZs can be used to offset encroachment by Russia and China and Iran within region. Finally, use of SEZs through Compacts anchors the Middle East economically to the EU.

Prioritize United States Foreign Assistance, Foreign Military Assistance, and Economic Assistance to Countries Supporting SEZs

The United States should provide additional financial incentives for nations to participate in compacts and SEZs by prioritizing foreign and military assistance to those countries willing to participate. Additionally, United States assistance can be focused on establishment of SEZ mechanisms and significantly augment European contributions creating the momentum necessary to achieve success. Admittedly, SEZ will take time to achieve impacts. Accordingly, during implementation, compact nations should consider the deployment of multinational forces as a policy option to the geographic regions where SEZs will be established to reduce violence and provide tangible sign of international commitment to the successful resolution of the conflict in Syria.

4.3 Build UNSC consensus for the deployment of Multinational Peacekeeping Forces in SEZs to Reinforce Strategic Relationships, Monitor SEZs, and Reduce Violence

Multinational Peacekeeping Force. Displaced populations live in ungoverned or lightly governed geographical regions. Lack of rule of law or clear authority presents opportunities for violent extremists to utilize displaced populations as safe havens. Policing displaced populations with national armed forces keeps these populations on edge as multiple state actors with conflicting self-interests continue to fight for disparate reasons.56 A credible multinational peacekeeping force tied to a geographic region and/or SEZ could help reduce violence and the use of these populations for political or military leverage. Use of a multinational force also keeps all parties focused on the common national security interests of preventing the resurgence of violent extremism vice taking sides in an intractable conflict in Syria. Moreover, UN Peacekeeping forces have valuable experience helping countries transition from conflict to peace. For example, UN Peacekeeping forces have been used to keep the peace between Israel and Egypt for decades. UN Security Council and General Assembly mandates coupled with the deployment of multinational peacekeepers can add further legitimacy and momentum to EU and United States efforts to establish SEZs.57 Essentially, the economic buffer created by SEZs can and should be augmented by an unbiased military force to enable military disengagement on all sides.

A credible multinational peacekeeping force tied to a geographic region and/or SEZ could help reduce violence and the use of these populations for political or military leverage. Use of a multinational force also keeps all parties focused on the common national security interests of preventing the resurgence of violent extremism vice taking sides in an intractable conflict in Syria.

4.4 Continue to Pursue a Middle East Strategic Alliance (MESA) to Maintain a Balance of Power within the Middle East

Unite MESA Against Common Security Threat. The United States should continue to pursue a regional security or economic alliance to support regional conflict resolution and prevention mechanisms. The resurgence of violent extremism through weaponized populations and mobile safe havens in the Middle East is a significant threat to the survival of all governments in the region. The threat of the resurgence of violent extremism coupled with external threats posed by great powers and internal threats posed by proxies and the nations of the Middle East could face another larger Arab Spring. Violent extremists organizations destabilize already fragile states and create the breeding ground for ever more radical groups.58 A regional strategic alliance or security architecture could prevent or mitigate future civil wars and regional conflicts.59 The United States has been actively supporting a Middle East Strategic Alliance (MESA) that includes all Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) states—Bahrain, Kuwait, Oman, Qatar, Saudi Arabia, and the UAE—as well as Egypt, Jordan, and the United States.60 Here, MESA would need to include Iraq in order to achieve threat mitigation more holistically as it relates to Syria. MESA could link military security to political and economic security while advancing the priorities and acknowledging the constraints of prospective Arab member states.61 Working in concert with SEZs, MESA could provide an additional layer of security and stability necessary for peace.

4.5 Consider Pluralistic Legal Mechanisms to Adjudicate Foreign Terrorist Issues with International Monitors

Foreign Terrorist Fighter Disposition

Foreign terrorist fighters significantly increase the level and duration of conflict wherever they are found. In Syria there remain some two thousand foreign terrorist fighters under SDF control. Any policy for the reduction of threats arising out of Syria must include a foreign terrorist fighter disposition option. Foreign fighters raise a multitude of difficult legal and pragmatic issues that paralyze international action. Foreign terrorist fighters must be addressed to ensure reductions in violence can be maintained when economic and diplomatic mechanisms mature. As a result of years of negotiations, only a couple of viable policy options remain to address the foreign terrorist problem. Repatriation is becoming less tenable as countries have been stripping citizenship of nationals joining terrorist causes abroad.62 Accordingly, only two practical options remain. Foreign terrorist fighters detained in Syria can either be turned over to the Assad regime and prosecuted in accordance with Syrian law or they can be transferred to Iraq where they can be prosecuted under the supervision of an international monitor. Both options are fraught with risk but remain the best of a host of bad options.

Syrian Prosecution with International Monitor

If Assad remains in power, then the international community will have to negotiate with him on a resolution of the conflict. Appropriate disposition of foreign terrorist fighters through the Syrian criminal justice system can provide Assad with a mechanism to demonstrate good faith to the international community while peace negotiations continue.

Iraqi Prosecution with International Monitor

In the alternative, foreign terrorist fighters can be transferred to Iraq for prosecution. The United States has already been in negotiation with Iraq for such support. This option provides additional assurances that detainees will be subjected to a legitimate legal process for case adjudication. Adding international legal monitors could ensure appropriate legal standards are complied with while opening the door for post-trial transfer to countries of origin who could adopt the legal disposition and help implement disciplinary actions.

International Hybrid Courts

Regardless, the United States cannot rely solely on repatriation as the sole means to address the large-scale foreign terrorist fighter problem scattered throughout Syria and embedded in displaced populations throughout the region. Scholars argue that such hybrid courts are precedential for new hybrid courts to try foreign terrorist fighters who fought for or with the Islamic State without having to prove war crimes or crime against humanity.63 Perhaps it is time that the international community consider a hybrid court model that works within a pluralistic legal model where criminal cases depending on the level of the criminal acts, can be parsed out to different components of the pluralistic legal system functioning in most middle eastern societies today. Cases can be adjudicated much more efficiently, and the entire system would benefit from legitimacy garnered from the use of local and international legal standards. Utilizing such systems would not alleviate all issues with evidence collection and authentication but would like increase participation by witnesses who would be otherwise skeptical of a contemporary legal system.

5. Conclusion

Addressing the national security risks posed by weaponized populations and mobile safe havens is a United States strategic imperative. The resurgence of violent extremist organizations in the Middle East poses regional and global national security threats. If a resolution is not achieved, violent extremist threats to the United States, Europe, and the Middle East arising out of Syrian region will only increase over time. The major problem for the United States as it relates to Syria is the fact that the mass displacement and migration of Syrians both internally and externally has created mobile safe havens for violent extremist ideology to not only survive but also grow and flourish. Focused economic policies coupled with enhanced strategic and regional relationships in the Middle East will not only reduce the precursors for conflict for generations but also guarantee stability throughout the region while offsetting the growing influence of Russia and Iran. The foreign policy options listed above outline a long-term approach that together can reduce violence in the region through economic and military containment to facilitate conflict resolution and reconciliation.

Broadbent , Robert . “Syria Redux: Preventing the Spread of Violent Extremism Through Weaponized Populations and Mobile Safehavens.” May 2020

- “UN News, December 14, 2017, https://news.un.org/en/focus/syria.

- “Definition of WEAPONIZE,” accessed February 15, 2020, https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/weaponize.

- “How Many IS Foreign terrorist fighters Are Left?,” BBC News, February 20, 2019, sec. Middle East, https://www.bbc.com/news/world-middle-east-47286935.

- “Options for Dealing with Islamic State Foreign terrorist fighters Currently Detained in Syria,” Combating Terrorism Center at West Point, May 29, 2019, https://ctc.usma.edu/options-dealing-islamic-state-foreign-fighters-cur….

- “From Daesh to ‘Diaspora’ II: The Challenges Posed by Women and Minors After the Fall of the Caliphate,” Combating Terrorism Center at West Point, July 18, 2019, https://ctc.usma.edu/daesh-diaspora-challenges-posed-women-minors-fall-….

- UN Security Council Res. 2178 (2014) preamble, accessed October 29, 2019, https://www.un.org/sc/ctc/wp-content/uploads/2015/06/SCR-2178_2014_EN.p….

- David Malet, Foreign terrorist fighters: Transnational Identity in Civic Conflicts (Oxford University Press, 2013), https://www-oxfordscholarship-com.ezp-prod1.hul.harvard.edu/view/10.109….

- David Malet, Foreign terrorist fighters: Transnational Identity in Civic Conflicts (Oxford University Press, 2013), 40, 54, https://www-oxfordscholarship-com.ezp-prod1.hul.harvard.edu/view/10.109….

- Malet, 6.

- “Options for Dealing with Islamic State Foreign terrorist fighters Currently Detained in Syria.”

- Jim Mattis, “Summary of the 2018 National Defense Strategy,” available at https://dod.defense.gov/Portals/1/Documents/pubs/2018-National-Defense-…, last accessed 30 October 2019. (Terrorism remains a persistent condition driven by ideology and unstable political and economic structures, despite the defeat of ISIS’s physical caliphate).

- C. T. C. Admin, “Foreign Terrorist Fighters,” United Nations Security Council Counter-Terrorism Committee (blog), accessed October 29, 2019, https://www.un.org/sc/ctc/focus-areas/foreign-terrorist-fighters/.

- “Ctc_cted_fact_sheet_designed_ftfs_updated_15_november_2018.Pdf,” accessed October 29, 2019, https://www.un.org/sc/ctc/wp-content/uploads/2019/06/ctc_cted_fact_shee….

- “May/June 2019,” Combating Terrorism Center at West Point, May 29, 2019, https://ctc.usma.edu/may-june-2019/.

- “Turkey’s Erdogan Heading to Brussels to Discuss Refugee Crisis,” accessed March 9, 2020, https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2020/03/turkey-erdogan-discuss-migrant-i….

- Norimitsu Onishi and Elian Peltier, “Turkey’s Deportations Force Europe to Face Its ISIS Militants,” The New York Times, November 17, 2019, sec. World, https://www.nytimes.com/2019/11/17/world/europe/turkey-isis-fighters-eu….

- “Country Reports on Terrorism 2017,” United States Department of State (blog), accessed February 15, 2020, https://www.state.gov/reports/country-reports-on-terrorism-2017/.

- “Turkey’s Erdogan Heading to Brussels to Discuss Refugee Crisis.”

- “NSS-Final-12-18-2017-0905.Pdf,” accessed February 16, 2020, https://www.whitehouse.gov/wp-content/uploads/2017/12/NSS-Final-12-18-2….

- “Mattis - Summary of the 2018 National Defense Strategy.Pdf,” 9, accessed October 30, 2019, https://dod.defense.gov/Portals/1/Documents/pubs/2018-National-Defense-….

- Henry A. Kissinger, “A Path Out of the Middle East Collapse,” Wall Street Journal, October 16, 2015, sec. Opinion, https://www.wsj.com/articles/a-path-out-of-the-middle-east-collapse-144….

- Frank Ledwidge, Rebel Law: Insurgents, Courts and Justice in Modern Conflict (London: Hurst & Company, 2017), 34.

- “Accountability for Islamic State Fighters: What Are the Options?,” Lawfare, October 11, 2019, https://www.lawfareblog.com/accountability-islamic-state-fighters-what-….

- “Accountability for Islamic State Fighters.”

- Mattis, “Summary of the 2018 National Defense Strategy.”

- “The Islamic State and WMD: Assessing the Future Threat,” Combating Terrorism Center at West Point, January 19, 2016, https://ctc.usma.edu/the-islamic-state-and-wmd-assessing-the-future-thr….

- “Country Reports on Terrorism 2017.”

- Mattis, “Summary of the 2018 National Defense Strategy.”

- “Iranian General Transformed Syria’s War in Assad’s Favor,” AP NEWS, January 7, 2020, https://apnews.com/a0557de2499d53eb9d298bbea35bb9d8.

- Dmitriy Frolovskiy, “What Putin Really Wants in Syria,” Foreign Policy (blog), accessed March 9, 2020, http://foreignpolicy.com/2019/02/01/what-putin-really-wants-in-syria-ru….

- Deutsche Welle (www.dw.com), “Syria Conflict: What Do the US, Russia, Turkey and Iran Want? | DW | 23.01.2019,” DW.COM, accessed March 9, 2020, https://www.dw.com/en/syria-conflict-what-do-the-us-russia-turkey-and-i….

- “Turkey’s Erdogan Heading to Brussels to Discuss Refugee Crisis.”

- Mattis, “Summary of the 2018 National Defense Strategy.”

- Analysis by Nick Paton Walsh CNN International Security Editor, “For the First Time in 9 Years, Two Nation States Are Going Toe-to-Toe in Syria,” CNN, accessed February 15, 2020, https://www.cnn.com/2020/02/12/middleeast/syria-turkey-war-analysis-wal….

- CNN.

- Ishaan Tharoor closeIshaan TharoorReporter covering foreign affairs, geopolitics, and historyEmailEmailBioBioFollowFollow, “Analysis | Europe Can’t Wish Away Syrian Refugees,” Washington Post, accessed March 7, 2020, https://www.washingtonpost.com/world/2020/03/03/europe-cant-wish-away-s….

- affairs, geopolitics, and historyEmailEmailBioBioFollowFollow.

- Adam Taylor closeAdam TaylorForeign reporter who writes about a variety of subjectsEmailEmailBioBioFollowFollow, “Analysis | The Idlib Crisis Is a Reminder That the Syrian War Is Not Over,” Washington Post, accessed March 7, 2020, https://www.washingtonpost.com/world/2020/02/06/idlib-crisis-is-reminde….

- “Turkey Says It Will Let Refugees into Europe after Its Troops Killed in Syria,” Reuters, February 29, 2020, https://uk.reuters.com/article/uk-syria-security-idUKKCN20L37H.

- “Turkey-Syria Offensive: What Are ‘Safe Zones’ and Do They Work? - BBC News,” accessed March 9, 2020, https://www.bbc.com/news/world-middle-east-50101688.

- Steven Simon and Jonathan Stevenson, “The End of Pax Americana,” February 4, 2016, https://www.foreignaffairs.com/articles/middle-east/end-pax-americana.

- “World Refugee Day: UN Calls Syria ‘worst Humanitarian Disaster’ since Cold War,” Christian Science Monitor, June 20, 2013, https://www.csmonitor.com/USA/Foreign-Policy/2013/0620/World-Refugee-Da….

- “NATO Heeds Trump’s Call to Be ‘more Involved’ in Middle East,” accessed January 22, 2020, https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2020/01/nato-heeds-trump-call-involved-m….

- Robyn Dixon et al., “In Syria’s Ravaged Idlib, Russian Airstrikes Underscore Wider Strategies in Region,” Washington Post, accessed March 7, 2020, https://www.washingtonpost.com/world/middle_east/in-syrias-ravaged-idli….

- “Russia, Turkey, Iran Hold 14th Round Of Talks On Syria War In Kazakhstan,” RadioFreeEurope/RadioLiberty, accessed January 24, 2020, https://www.rferl.org/a/russia-turkey-iran-hold-14th-round-of-talks-on-….

- “Syria: Lack of Consensus Following Face-to-Face Talks, Underscores Need for Broader Process,” UN News, December 20, 2019, https://news.un.org/en/story/2019/12/1054131. (“While a Constitutional Committee cannot solve the crisis, it can help foster the trust and confidence.”)

- Lindsey K Barr, “Syrian Refugees in Jordan: Special Economic Zones as an Economic Action Plan,” n.d., 105.

- Lauren Van Metre and Linda Bishai, “Why Violent Extremism Still Spreads,” Just Security, March 11, 2019, https://www.justsecurity.org/63169/violent-extremism-spreads/.

- “Refugee Compacts: Addressing the Crisis of Protracted Displacement,” Center For Global Development, 5, accessed October 28, 2019, https://www.cgdev.org/publication/refugee-compacts-addressing-the-crisi….

- “Refugee Compacts,” 17.

- “Refugee Compacts,” 6.

- “Refugee Compacts,” 9.

- Jackline Wahba, “Why Syrian Refugees Have No Negative Effects on Jordan’s Labour Market,” The Conversation, accessed November 5, 2019, http://theconversation.com/why-syrian-refugees-have-no-negative-effects….

- Kemal Kirişci and Gokce Uysal Kolasin, “Syrian Refugees in Turkey Need Jobs,” Brookings (blog), September 11, 2019, https://www.brookings.edu/blog/order-from-chaos/2019/09/11/syrian-refug….

- Caitlin Oprysko, “Trump Gives Turkish President a Warm Welcome despite Lawmakers’ Dissent,” POLITICO, accessed November 20, 2019, https://www.politico.com/news/2019/11/13/trump-turkish-president-070831. (“Instead, he announced that both countries would begin work on a $100 billion trade deal, applauded Erdogan for upping Turkey’s contributions to NATO and thanked him for his country’s help in the fight against ISIS. “Turkey, as everyone knows, is a great NATO ally,” Trump said in a joint news conference with Erdogan.”).

- Daniel Davis, “Daniel Davis: All US Troops Should Leave Syria—We Shouldn’t Get Sucked into War,” Text.Article, Fox News, February 29, 2020, https://www.foxnews.com/opinion/daniel-davis-all-us-troops-should-leave….

- “United Nations Peacekeeping,” United Nations Peacekeeping, accessed January 25, 2020, https://peacekeeping.un.org/en/node.

- Daniel Byman, “Beyond Counterterrorism,” Foreign Affairs 94, no. 6 (December 11, 2015): 11–18.

- Byman.

- Yasmine Farouk and Yasmine Farouk, “The Middle East Strategic Alliance Has a Long Way To Go,” Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, accessed January 26, 2020, https://carnegieendowment.org/2019/02/08/middle-east-strategic-alliance….

- Farouk and Farouk.

- “Northeastern Syria: Complex Criminal Law in a Complicated Battlespace,” Just Security, October 28, 2019, https://www.justsecurity.org/66725/northeastern-syria-complex-criminal-…. (“Many European states have refused to take their fighters back, citing an inability to prove cases against suspects and a lack of resources to place returning jihadists under constant surveillance. The United States has warned that a failure to repatriate these individuals could result in them simply going free. Regardless of which countries try which members of ISIS, the international community needs to begin taking more decisive action if it is serious about bringing members of ISIS to justice. Without effective prosecutions, there is a danger of ISIS members going free.”Id.).

- “Options for Dealing with Islamic State Foreign terrorist fighters Currently Detained in Syria.”